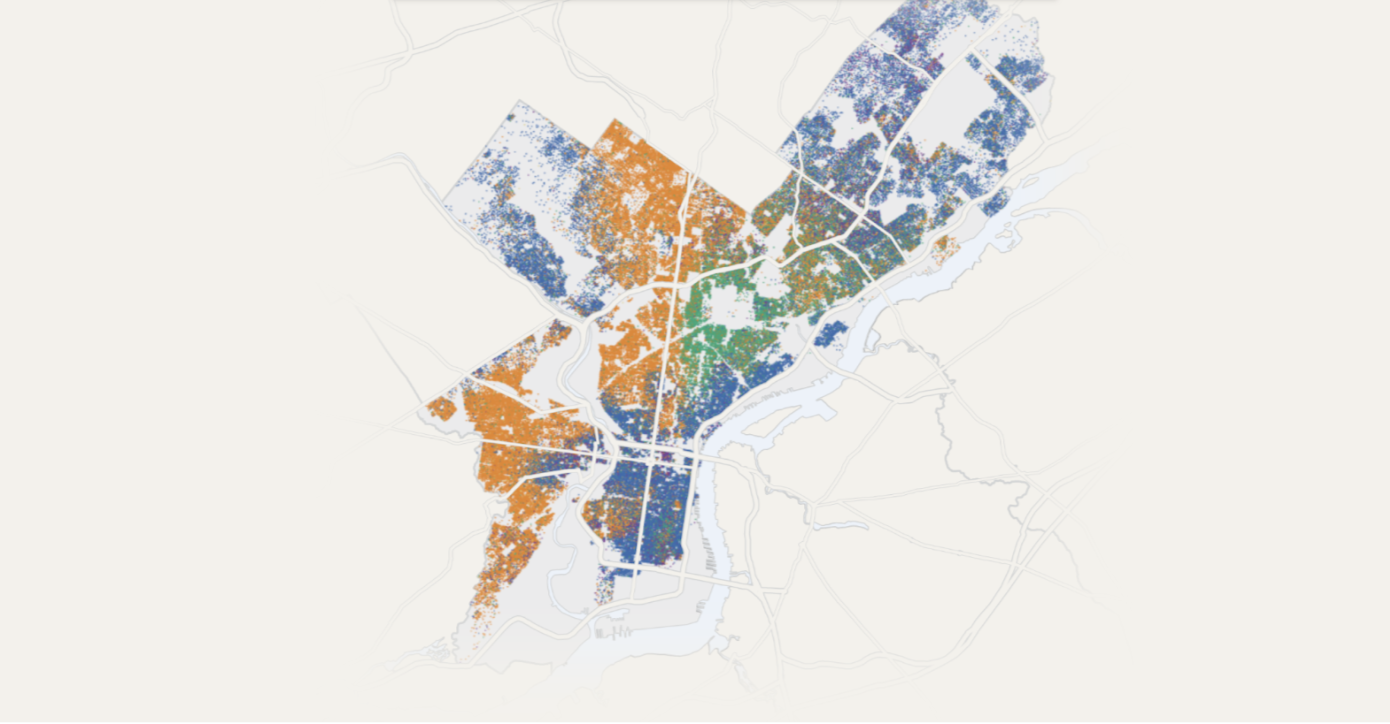

Figure 1 (Key: Blue: white residents, Orange: Black residents, Green: Hispanic residents, Purple: Asian residents, Yellow: Other) (DeMoe, Duchneskie).

Despite being one of the most racially diverse cities in the United States, Philadelphia is extremely racially segregated. The enormity of this problem is compounded manifold by the ever-growing issue of gentrification. In areas of Philadelphia whose residents are primarily Black and Hispanic, arrest rates are significantly higher than in primarily white parts of the city (Public Data Dashboard). Over the past few years, the University of Pennsylvania area in University City and other college communities have seen drastic increases in both police presence and arrest rates as gentrification has begun to force out Black residents and establishments. In recent years, this gentrification has only served to exacerbate Philadelphia’s problem with racial segregation, the wealth gap, and the effects of police presence on communities of color. Reallocating money from the police department to community-based services is the most productive way to begin to combat these pressing issues.

Racial segregation in Philadelphia has led to a divided city. In 2021, the Philadelphia Inquirer mapped out Philadelphia’s racial composition. The map (Figure 1) depicts sharply contrasting colors, which represent white, Black, Asian, and Hispanic races. Most parts of Philadelphia are overwhelmingly occupied by an individual race, and the few areas of Philadelphia with interracial communities are primarily composed of Hispanic and Black residents (Shukla, Bond).

Today’s racial segregation in Philadelphia is a direct result of racist practices like redlining, which perpetuated both a racial divide and a class divide. Take two zip codes in Northwest Philadelphia: 19118, a primarily white neighborhood, and 19138, a primarily Black neighborhood. Despite being only two miles apart, the median family income for residents of 19118 is $123,780 but only $50,554 for residents of 19138 (Shukla, Bond). This is not a unique phenomenon, as wealth is inextricably tied to race in communities across the city. Thus arises the problem of gentrification.

Like in all major American cities, gentrification is becoming a more pressing problem every day for many Philadelphia residents. Because of the racial and economic underpinnings of Philadelphia’s segregation, poor Black and Hispanic residents often suffer the most. There are often only two possible outcomes of gentrification for Black and Hispanic residents: forced removal or over policing. In the first outcome, Black and Hispanic residents and establishments are often forced out as housing and property prices skyrocket, and white residents and establishments take their place. In University City, The University of Pennsylvania is seen as a catalyst for gentrification. Because Penn is a predominantly white institution (PWI), many of its white students are resistant to the local community, much of which is historically Black. The wealthy, white Penn students have not only created a sizable white community, but they are a community that does not interact with the local Black-owned businesses. As a result, housing prices skyrocket with the influx of white residents, and non-white businesses fail. Many Black and Hispanic residents who cannot afford these higher prices are forced to leave (Ratner). Those who stay are forced to contend with an increased police population.

As the new wealthy, white population grows inside of a community that has been historically Black, Hispanic, and working-class, so does the sense of fear within the white residents. This sense of fear is rooted in classism and racism but is often not recognized by white residents as such. Rather, this fear is seen as a legitimate problem, and thus the police population is supplemented to quell the fears of white residents. However, white residents are often irrationally afraid of their Black and Hispanic neighbors, and thus these already marginalized groups are often targeted by the police, an institution with its own deeply rooted racist ties. According to BillyPenn, the Penn police force is the second-largest police force in the country, with a police force that clocked 120,000 neighborhood patrol hours in 2018 (Winberg). Because of the increase in policing in recent years of the University City neighborhood, arrest rates are also on the rise. The Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office reported 1,321 arrests in District 03 (the home of University City) in 2018 (Public Data Dashboard).

This issue of over policing and high arrest rates is nothing new to Black and Hispanic communities in Philadelphia. Districts 15, 24, and 25 (primarily composed of Kensington, North Philadelphia, and Near Northeast Philadelphia), all with high numbers of Black and Hispanic residents, have consistently maintained some of the highest arrest rates in Philadelphia for years, with other Black and Hispanic communities never falling far behind (Public Data Dashboard). Since 2014, the majority of arrests in Philadelphia have been drug-related offenses. Drug possession makes up the majority of drug-related arrests nearly every year since 2014 (Public Data Dashboard). Many of these arrests, especially arrests for possession of drugs and other nonviolent offenses, could be prevented by defunding the police. If police funding were reallocated to services and initiatives to benefit the poor Black and Hispanic communities often targeted by police, crime rates would drop, and over policing would cease to be an issue (Khan).

Take the criminalization of drug use as an example. Right now, drug users, especially those who are Black or Hispanic, are criminalized, which only makes the problem worse. If we invested in rehabilitation instead of police to combat this issue, drug users could recieve help rather than punishment. This method is reconciliatory rather than punitive, and can be applied broadly across many injustices exacerbated by over policing, including disparities in both education and healthcare. Reinvesting in poor communities of color in Philadelphia would help to rectify the problems of gentrification and segregation, which are partially upheld by the class divides between neighborhood residents and prevent the problem of over policing from continuing to multiply exponentially.